8.7 million year-old fossil rewrites the story of human evolution

New fossil discoveries from Turkey challenge the belief that hominines originated in Africa, pointing to Europe as a pivotal site for early evolution.

|

| Fossils from Turkey, including Anadoluvius turkae, suggest hominines may have evolved in Europe before migrating to Africa, (CREDIT: CC BY-SA 4.0) |

The origin of the hominine lineage—encompassing modern humans, chimpanzees, gorillas, and their ancestors—is one of paleoanthropology's most debated topics, thebrighterside.news.

For over a century, the prevailing view has linked the evolutionary roots of hominines to Africa, where the earliest fossils of this group have been found. However, recent fossil discoveries from the late Miocene in Europe and the eastern Mediterranean suggest a radically different narrative, one that places Europe at the center of early hominine evolution.

Newly unearthed fossils, including a nearly complete cranium of Anadoluvius turkae from Turkey, have shifted the focus to Europe as a potential birthplace of hominines. These findings not only highlight the diversity of apes in the region but also suggest a migration pathway that challenges traditional theories of human ancestry.

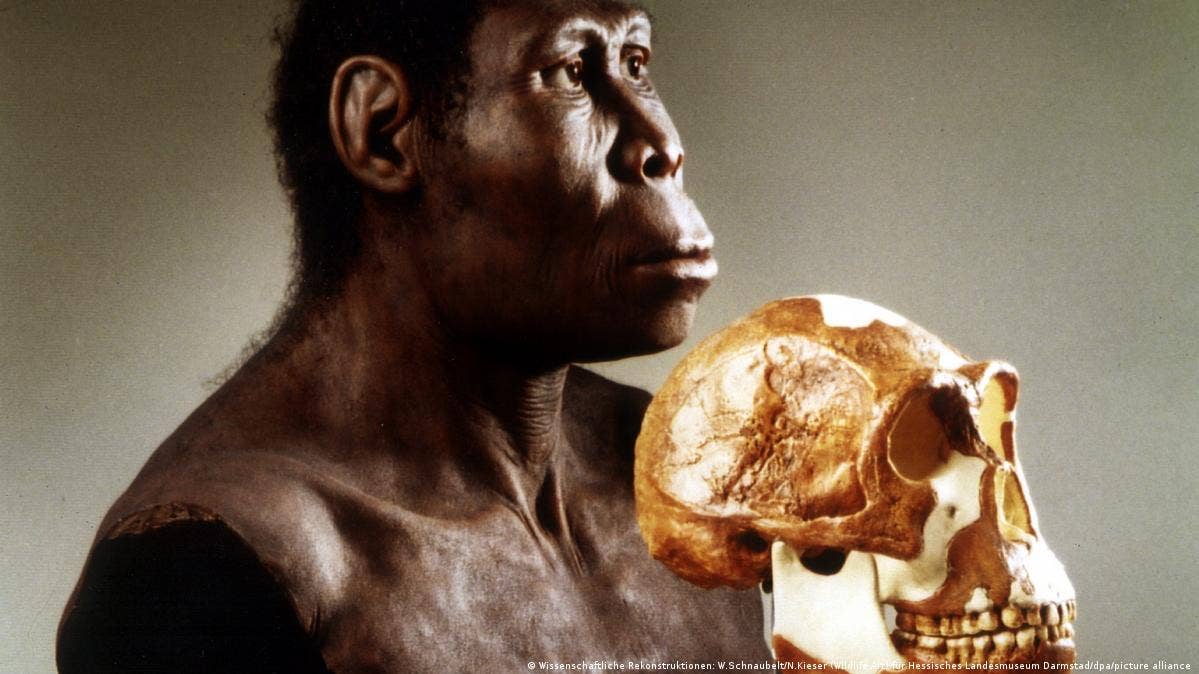

At the heart of this groundbreaking study is Anadoluvius turkae, a fossilized partial cranium discovered in 2015 at the Çorakyerler site near Çankırı, Turkey. This specimen, remarkably preserved and dated to approximately 8.7 million years ago, offers unparalleled insights into the morphology of one of Europe’s last great apes.

Researchers meticulously analyzed the cranium, which included much of the face and the anterior part of the braincase. This level of preservation allowed scientists to reconstruct the anatomy of Anadoluvius with an unprecedented level of detail. The cranium's robust features suggest an ape with a body size similar to a large male chimpanzee, weighing between 110 and 132 pounds.

The fossil also reveals critical traits associated with hominines, such as specific configurations of the dental roots, cranial structure, and facial morphology. These features distinguish Anadoluvius from other Miocene apes like Ankarapithecus, which lacks hominine characteristics, and align it more closely with Ouranopithecus and Graecopithecus, other eastern Mediterranean apes.

A European Origin for Hominines?

The analysis of Anadoluvius turkae supports the hypothesis that hominines may have evolved in Europe and later migrated to Africa. According to the research team, this scenario is more parsimonious than the idea that hominines evolved in Africa and then dispersed to Europe only to face extinction.

Instead, they propose that Europe was home to a thriving population of hominines for millions of years before environmental changes prompted their migration to Africa.

This perspective is bolstered by the phylogenetic analysis of Anadoluvius and related fossils. Using sophisticated software, the researchers input morphological traits from Anadoluvius alongside those of other known fossil and extant hominoids.

The results placed Anadoluvius firmly within the hominine lineage, indicating a closer evolutionary relationship with African apes and humans than with other apes of the Miocene era.

Mediterranean Diversity: A Melting Pot of Miocene Apes

The discovery of Anadoluvius turkae underscores the rich diversity of late Miocene apes in the eastern Mediterranean. Fossils from this region, dating between 9.6 and 7.2 million years ago, reveal a broader range of ape species than previously appreciated.

Ouranopithecus, discovered in Greece and Bulgaria, was once considered the primary representative of hominines in this region. However, the addition of Anadoluvius and a reassessment of specimens like Graecopithecus indicate that multiple taxa existed, forming an evolving lineage.

This diversity suggests that the eastern Mediterranean served as an important ecological corridor, connecting populations in Europe and Asia.

In Turkey, the Çorakyerler site has emerged as a treasure trove of late Miocene fossils. Thousands of vertebrate remains have been unearthed, providing valuable context for the ancient ecosystems in which these apes lived.

The environment, characterized by dry forests and open landscapes, likely played a pivotal role in shaping the behavior and morphology of these early hominines. Unlike their arboreal relatives, Anadoluvius and its kin appear to have spent considerable time on the ground, adapting to a more terrestrial lifestyle.

Environmental Shifts and Migration

The evolutionary trajectory of early hominines was influenced by profound environmental changes during the late Miocene. Shrinking forests and expanding grasslands created new ecological pressures, forcing populations to adapt or migrate.

Professor David Begun, a biological anthropologist at the University of Toronto and a lead researcher on the study, explains, “The members of this radiation to which Anadoluvius belongs are currently only identified in Europe and Anatolia.” He adds that fluctuating environmental conditions likely facilitated the migration of these apes into Africa, where they gave rise to later hominine species.

This migration was not an isolated event. Fossil evidence indicates that many mammals moved between Europe and Africa during this period, suggesting a dynamic interchange of species driven by shifting climates and habitats.

A Turning Point in Understanding Human Evolution

The implications of these findings are profound. If hominines did indeed originate in Europe, it would necessitate a reevaluation of the timeline and geographical context of human evolution. While the discovery of Anadoluvius turkae is a significant piece of the puzzle, researchers emphasize that more evidence is needed to confirm the connection between European hominines and their African descendants.

“This new evidence supports the hypothesis that hominines originated in Europe and dispersed into Africa along with many other mammals between nine and seven million years ago, though it does not definitively prove it,” says Prof. Begun. “For that, we need to find more fossils from Europe and Africa between eight and seven million years old to establish a definitive connection between the two groups.”

The discovery of Anadoluvius turkae highlights the ever-changing nature of evolutionary science. Each new fossil adds complexity to our understanding of the past, challenging established theories and sparking fresh debates. As Prof. Begun and his team continue their work, they remind us that the story of human origins is far from complete.

“The completeness of the fossil allowed us to do a broader and more detailed analysis,” notes Prof. Begun. “The face is mostly complete, after applying mirror imaging. The new part is the forehead, with bone preserved to about the crown of the cranium. Previously described fossils do not have this much of the braincase.”

As more fossils are unearthed and analyzed, the picture of early hominine evolution will become clearer. For now, discoveries like Anadoluvius turkae serve as a testament to the complexity and richness of our shared history.

Коментарі

Дописати коментар